I’ll admit it: I am a victim to clickbait. This headline popped up in my newsfeed:

Are You Making This Big Mistake with Wine Corks?

and like a dope, I fell for it. But you won’t believe what happens next!

What happens is, I’m not going to link to the article. It doesn’t deserve my help generating clicks. You can find it yourself if you like, but I’m going to take some care to interpret it here for you in case you hate clickbait too.

Pimped out as their ‘Wine Wise Guy’, their author wrote an article that illustrates everything wrong with the concept of the modern sommelier and showed himself as a prime example of the self-important, narcissistic jackassery that follows it around like a foul stench.

What’s wrong with sommeliers? Nothing actually. Sommelier is a job description, and it means ‘guy who sells wine in a restaurant’. It’s as descriptive as ‘receptionist’, or ‘usher’, or ‘sanitation engineer’.

It doesn’t mean a damn thing more: guy who sells wine.

Unfortunately, in our celebrity and reality show obsessed culture the concept of sommelier as something ‘other’, something aspirational, something to be revered and worshipped has taken hold. Several things have conspired to create a cult of personality around ‘somms’, not the least of which are the sommeliers themselves. But they’re not the worst offenders: the worst offenders are the schools that offer sommelier ‘courses’, offering to teach everything about wine and to turn you into a wine professional.

These courses force a hapless student to memorise thousands of facts about wine regions and styles, most of which might be interesting in a Jeopardy Daily Double kind of way, but are useless in the real world, and are tarted up as trick questions, the better to exclude people who haven’t paid the tens of thousands of dollars for the course, or memorised a stagnant morass of factoids like an obedient Labrador Retriever doing tricks.

The thing to remember about sommelier programs is that they’re not actually recognised as an official education by anyone who matters. Sure, doing your time in wine prison is like a union card to enter the world of selling wine in a restaurant, but unlike a Red Seal for a Chef (transferable around the world), there is no formal recognition of this nonsense, and different schools of sommelier-dom don’t teach the same things.

Lest any somm-worshipper out there get in a flounce and accuse me of sour grapes (haha, see what I did there?) because I don’t hold that job description, let me reassure you: I am a recovering sommelier. At one point in my life I sold wine in the most overblown, pretentious, expensive restaurant you could name. Back in the early 80’s the soup was twenty-five bucks.

This is the first time I’ve admitted to doing that job in decades, because even back then it was a soiling experience, mainly because the owner was a fraud who kept the wine in a furnace room or a walk-in cooler, and 80% of the bottles that cost more than $40 were at our ‘other cellar’, which was the liquor store down the block, where the owner would sprint down to pick up a bottle as it was ordered. I did the job for a month before I quit in disgust to become a dishwasher instead.

When I had my first gig as GM of a resort hotel I took over the sommelier role and loved it. I got to help people enjoy wine by asking what they wanted and doing my best to give them exactly that. There’s no wrong way to enjoy wine, only the way the customer wants it. If they wanted red Bordeaux over ice, then I brought them ice. If they wanted Port with their fish, I made sure they knew what they were ordering and I served it. I had a bunch of backpackers come in who wanted kalimotxo, and when I found out it was cheap dry red and cola, I made up a pitcher. Why? Because I am not the arbiter of human taste or fashion: I am a service professional!

Which brings us back to the article. In it, the author first waxes his ego by mentioning in order a) how hard the exam was, b) how intimidating the examiners were, c) how obscure the questions were, and d) how much he hated serving wine to stupid peasants who came to the restaurant and expected him to serve wine.

Personally, I bundle most of these maneuvers into what I call “the frippery” of wine service: stuff that makes most people I know slink down in their seats in hopes that the sommelier will call on someone else to taste the wine.

Really? A quaint old ceremony, one that is the essence of the job makes him squirm? I wonder how he feels about the people who are paying him to do the job?

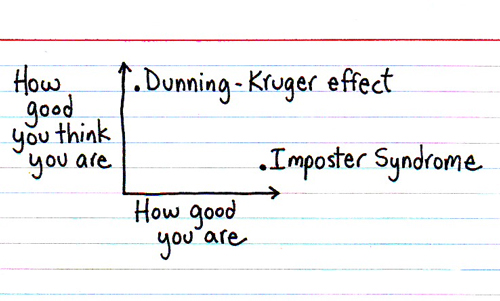

But then I see that person: The Imbiber. He’s the one—and it’s always a man—who relishes the pageantry of it all, the pomp and circumstance, who imagines that everyone else in the room is intently watching this noble ceremony take place. And when the sommelier places the just-pulled cork on the table to the right of the glass, The Imbiber picks it up ceremoniously, rolls it between his thumb and forefinger, and takes a deep, satisfying sniff.

The Imbiber deserves to be dunked in a barrel of wine.

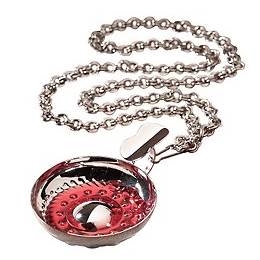

Rolling a cork—which is just a piece of bark from a cork tree, after all—between your thumb and forefinger is just plain silly. And sniffing it? Sillier. That is, unless (and this is an important unless) you’re the person pulling the cork.

Yes, murdering customers because they expect you to do a job, preciously described as being so haaaard is a completely reasonable response. After all, why make them happy when you can measure your manhood against theirs and make fun of them?

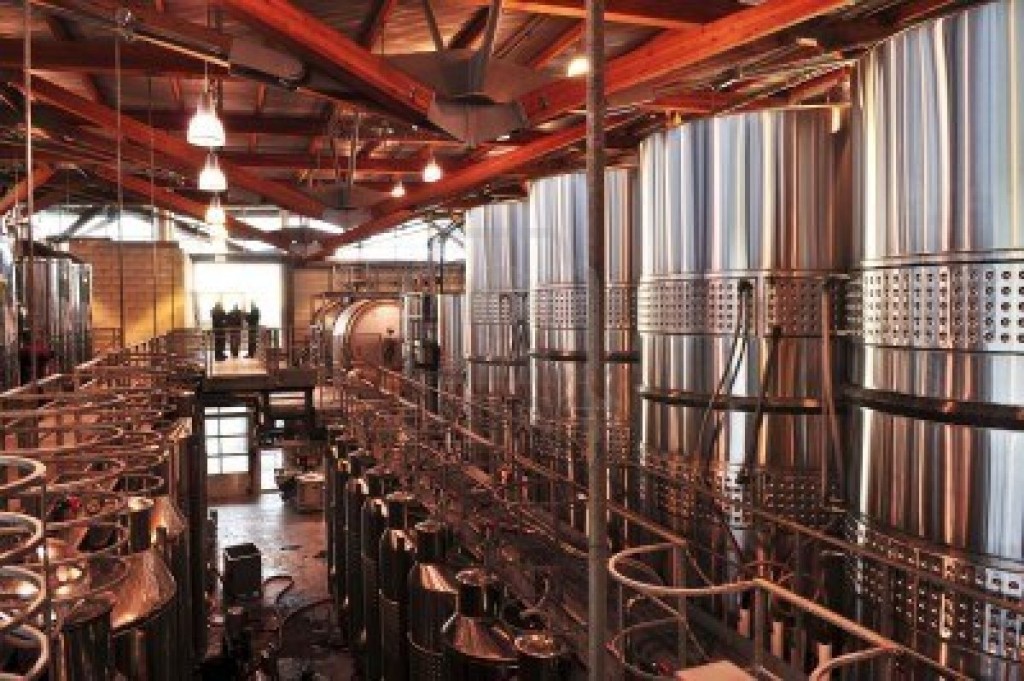

Know this: I like corks. I know a lot about corks. In my time in my industry, the companies I worked for made (aggregately) enough wine to fill more than a fifty million bottles per year, and we bought corks for them all. Over the course of a thirty-year career, that’s a lot of metric tonnes of cork. I’ve toured cork forests, cork factories, cork warehouses and dealt with almost every cork manufacturer on the planet. I know more about corks than the author of this article ever will, or can ever hope to. I not only examine, roll and sniff the cork from most bottles of wine that I am served, I habitually carry a razor-sharp knife and cut the cork in half to examine the inside for flaws and density.

Even if I weren’t a professional with a deep interest in the world market, I’d probably still be interested in the cork. It’s the only thing standing between the wine inside the bottle and a harshly cruel environment that wants to spoil it. If the cork looks compromised or has an odour (more on this in a minute) then I’m going to sit up and start paying attention to the process at hand: trying the wine to see if it’s a) what I ordered and b) in good condition.

The author goes on to pontificate why the consumer has no business assessing the cork. First, of course, he has to explain to us peasants what a corkscrew is and how it works, since as a professional, he’s sure that’s quite beyond us. Then he warns that he might not deign to hand you the cork at all:

It might fall apart because it’s too old; it might snap in half because it’s brittle; the center of it might disintegrate, because it’s soaked through and crumbly. If any of those things happen, there’s no cork to present to The Imbiber.

Wrong: if the cork crumbles, you immediately show it to the customer, perhaps carefully assembled on a napkin to keep the bits together. Why? Because he is buying that bottle of wine, and it’s his right as a consumer to see it. But he doesn’t see it that way: the mark he’s sneering at has no right to his own wine, just to the almighty somm’s opinion about it.

If I’m the server, yes, I’ll immediately smell the wet end to see if there are any “off” odors that might indicate the wine is flawed, damaged, or just plain dead. The wet end of a cork is still moist and porous, but the liquid at the tip either absorbs or dissipates pretty quickly. And a few seconds later, the cork smells like… cork.

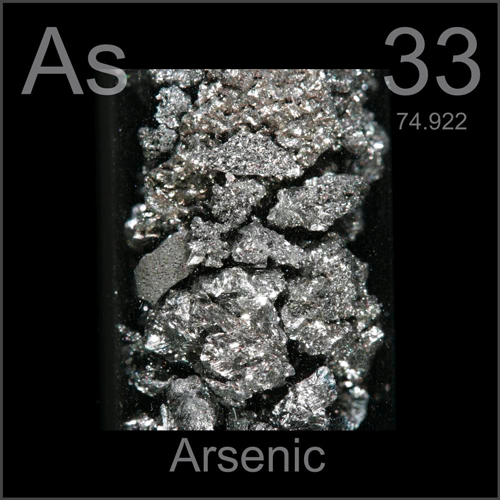

This is an easily dismissed falsehood: if the wine is contaminated by cork taint, the cork will smell like it, practically forever. This taint is 2,4,6 Trichloroanisole (TCA) and is caused by an interaction between chlorophenol compounds and corks or wood used in elevage, or processing wine. It’s a lot less common since cork producers stopped using chlorine to bleach corks, and started keeping sheets of cork bark off of the ground post-harvest/pre-processing (they can pick up a fungus off the ground that makes TCA contamination a lot more likely). Even in minute amounts (below the microgram level) TCA can ruin a good wine.

To sum up this whole sordid pile, articles like this, written by people who have an overweening, narcissistic view of their own worth and status are why I avoid modern sommeliers and their cult of celebrity. The job is exactly the same as the one done by the person who serves the bread, or the nice lady who takes the reservations.

If the bread guy started rolling his eyes, writing articles about how stupid people who eat bread are for asking for white or rye, or the reservation lady wrote snide blogs about how people who made reservations were dumbasses who really should let her handle things because they’re unqualified, the consumers who patronise those restaurants would lose their collective minds–as they should. But because some people buy into this cult of sommeliers and assume that they are the final word on how to drink wine, they get away with smug, nonsensical crap like this.

What’s the answer? I don’t have one, that’s for sure. However, a good first step is to avoid any restaurant that this guy works for. Also, if there’s a celebrity sommelier in a place you’re thinking of going to, don’t take any guff from them: you are buying that wine, and if you want to drink it out of a coffee mug, or eat the cork with a dab of mustard, you damn well do so.

I have been saying this for thirty straight years, and I’ll say it again: nobody can tell you how to enjoy wine–if they’re offering advice, trying to help you find a good match or something tasty in your price range, then they’re a good person, doing a good job and they deserve thanks. But if someone tries to tell you that you’re doing it wrong, or you’re not qualified to know your own mind and enjoy the things you like, as you like them . . . put your hand on your wallet and back out of the room, because they can’t be trusted.

One last thought, because as the man says, there always is one:

. . . unless you really like having sommeliers think you’re a twit. In that case, go right ahead, smell all the corks you want.

Dude, I’d rather you hated my guts than change anything about the way I enjoy wine to suit you.

All right, here’s the stupid article, if you must. Do me a favour and open it in an incognito browser. I don’t want to get this blog all sticky.