If you’ve just tuned in, be sure to read Making Mad Mead Part One and Part Two. As we return to our story, I am still a persona non grata with certain elements of the mead making subculture. Still, it’s nice to get mail from angry strangers, even if they can’t spell ‘nincompoop’.

Part three logically would be about processing my fermented Barkshack Ginger Mead. But first, a dark confession: I had already made a batch of mead, well before the delicious pink juice you saw in part one and two . . .

I was counting on my pal Jason to supply the attendees with great examples of well-made, modern mead done with the sensibility of someone who had a background both in wine and beer making, and who was good enough to sell mead commercially. He came through in a big way, with a generous shipment of his excellent meads.

I had commercial mead, I had my disruptive interpretation, and I also had a dark secret: I had already made an authentic prehistoric mead (sort of).

A couple of years ago I went on a hike in the Mayan jungles. After many amusing misadventures, including falling down a cenote and losing a car, I came across a little rural stand, way off the beaten path, that was selling honey. The folks in charge had only a modicum of English, so one of their kids explained to me that they gathered honey from wild hives in the jungle and sold it to tourists. They also traded it to folks in Oaxaca for coffee beans, which they roasted over wood fires–they made me the best cup of coffee I’ve ever had in my life.

I brought that bottle of honey home and tucked it into the cupboard, mainly as a curiosity: it was dark as the Coca-Cola that had previously occupied the bottle it came in, with a deeply aromatic caramel note and quite a lot of detritus from being an unfiltered product, as well as being unpasteurized unregulated and untouched by modern methodology. One day, however, I decided it was time to confront mead on its own turf, and formulated a plan to replicate the ancient ways. What can I say? It’s my attention surplus disorder leading me down every possible path.

By itself my Mayan honey wouldn’t be enough to make a satisfactory gallon of mead. Fortunately, I had a little bit more honey around that fit the bill. The first was a jar of Cuban honey (relax, I’m Canadian, we can trade with them), a gift from a friend. Low-tech processing ensured it was minimally altered from the natural state, although I’m pretty sure it got at least some filtering. There was finally a small dribble of honey from a jar of unpasteurized Elias organic honey that my wife may have used in a dessert without telling me. They’re a producer from Prince George British Columbia that’s got a very good reputation for quality. Together all of these honeys fit the bill for an old-style of honey, and would help me make a roughly traditional mead.

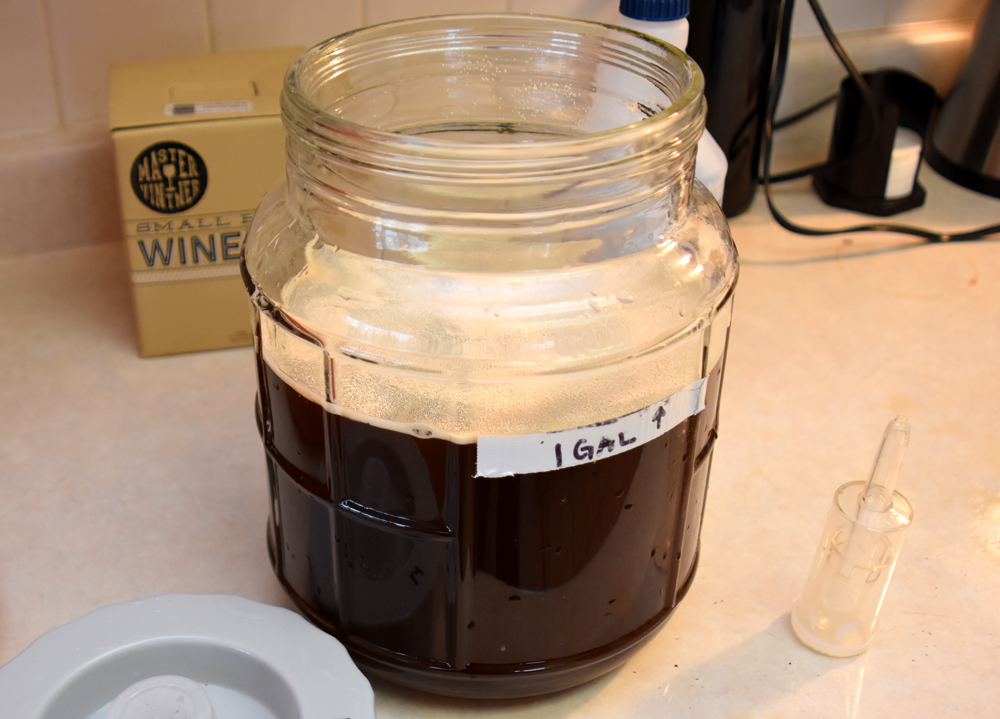

With just over three pounds of honey, I was ready to make a gallon of mead. I diluted the honeys with half a gallon of 55C/130F water, stirred to thoroughly mix, and cooled it to 24C/75F, then topped up with dechlorinated water to 4 litres/one gallon. Predicted SG on this would be around 1.100, so if it fermented completely dry it would make around 13-14% ABV. In keeping with primitive methods I didn’t bother with a hydrometer reading. If it was off there was no way to correct it in any case: I had no more honey suitable for the recipe.

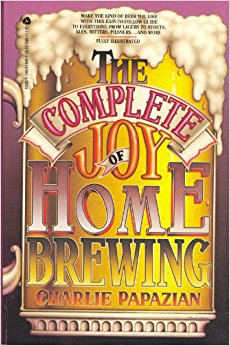

I chose to add yeast nutrient and a commercial yeast strain, because I wanted to give the fermentation a fighting chance. I used Fermaid K and Lalvin EC1118 Champagne yeast. If you’ve never used EC 1118, it’s . . . it’s kind of like the Incredible Hulk of yeast. It’s the strongest yeast, kills other yeast casually, ferments everything, and tolerates most conditions without producing off flavours. I could have left it outside to get a wild yeast, but we have hummingbirds. I could also have used bread yeast, but if you’re gonna add a commercial culture, you don’t bench the champ.

I pitched, fermented at 24C/75F, racked to two half-gallon jugs after four weeks of (very slow) fermentation and tucked it into my cellar to get a couple of months of age.

It wound up very nice and clear, and smelled awful, kind of like a combination of raisins and Porta-Potty: not in the enteric bacteria sense, but in the sense that I really wanted to do everything I could to avoid it. When the call came in from the PNWHC to do the seminar, I bottled up half of it and put it aside to age and left the rest under an airlock to do it’s thing for a year or two. We’ll see what it tastes like in 2018.

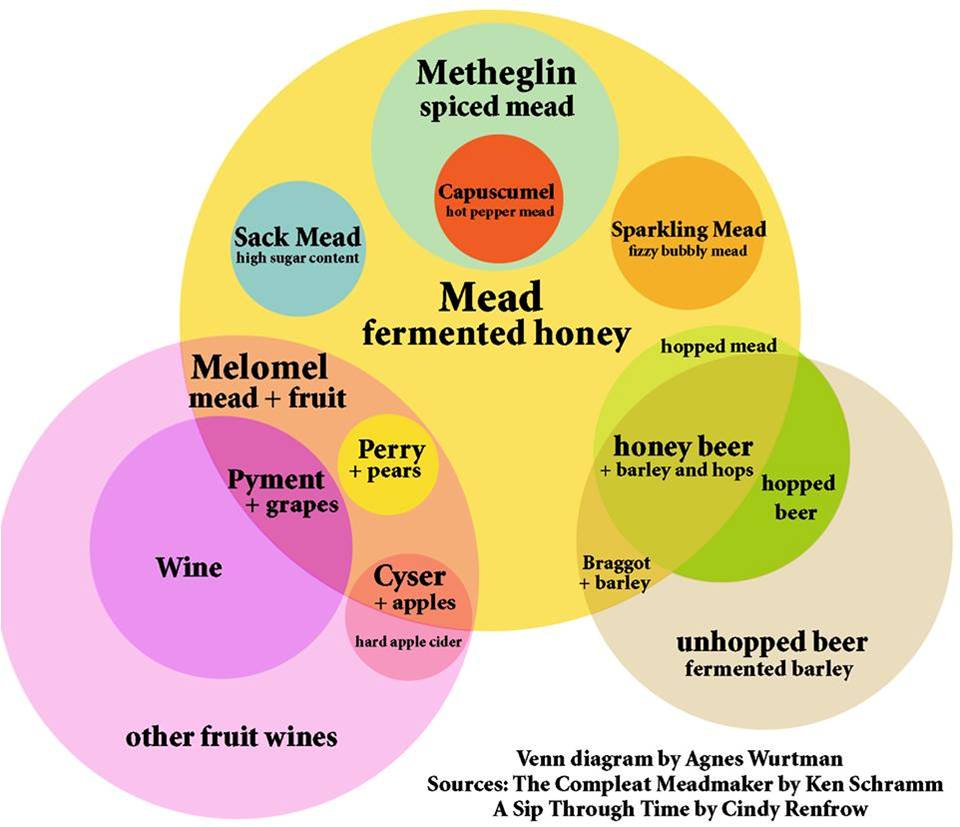

Snapping back in the present, in the next installment well get on with my Barkshack Ginger Mead. Processing that is going to involve fining, sterile filtering, stabilising with sulfite and sorbate, and back-sweetening with inverted sugar, and finally artificially carbonating in a keg with CO2. I’m hopeful that further explanations of what I’ve done will help mollify some of the mead makers who were concerned that I was going off half-cocked. I can assure all of them that I’ve never gone off more than one-quarter cocked in my life.