fail·ing

noun: a weakness, especially in character; a shortcoming. “Pride is a terrible failing..”

If you’re not failing every now and again, it’s a sign you’re not doing anything very innovative.

–Woody Allen

I was over at a neighbour’s house a little while ago and brought some of my homebrewed beer with me. His father, a very experienced brewer, was extremely complimentary about my Saison, a Belgian style of beer that features a low hop rate and a lot of spicy, fruity yeast character. I was momentarily filled with pride, because it was a pretty good beer, and it was the very first time I’d brewed it, and one of my peers was impressed. Yay me!

The next day I was working in my cellar and feeling pretty smug. As I racked a new brew into a keg I thought, “I can’t remember the last time I brewed a bad beer .”

That’s when I realised that I had a problem. Not failing was a sign that I was doing something terribly wrong.

For most people, failure is seen as a universally bad thing. Internet slang has produced a meme that has shortened criticism to the point where one can point to something and shout ‘FAIL!’, and it’s perfectly expressive opprobrium. Calling someone a failure is a pretty cutting insult.

The problem with this attitude is that a lack of failure doesn’t let us grow. Failure isn’t bad. If you want to learn something, really master it, the first thing you need to do is to figure out how not to do it. Thomas Edison made thousands of attempts to make a light bulb filament that would last more than a few seconds under current. When asked about his failure, he said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

Failure is a great motivator, it not only helps us grow, it also motivates us to try harder, to try again. But there’s an even more important benefit to failing: it frees you of pride–well, not pride precisely, because it’s fine to be proud of an accomplishment. What it really wipes out is hubris. Hubris, according to the interwebs, often indicates a loss of contact with reality and an overestimation of one’s own competence, accomplishments or capabilities, especially when the person exhibiting it is in a position of power.

Dang.

I am in theory an ‘authority’ on home fermentation. That’s what my career is based on, anyways, and it’s how I navigate most of my business interactions. I’m an excellent candidate for hubris. Luckily I mostly suffer from Imposter Syndrome, so I’m protected from hubris to some extent.

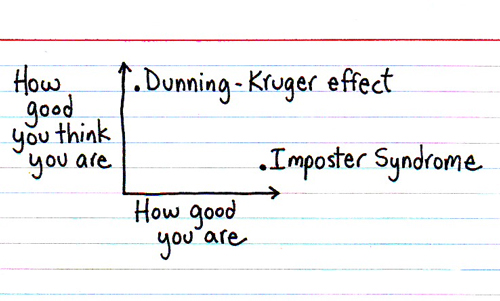

Never heard of it? Imposter Syndrome is the feeling that you’re not really competent in your given field, that you’ll be found out to be an imposter. This is most common among people who are actually competent, rather than those who are not–they’re covered under the Dunning-Kruger effect , which is when someone cannot recognise their incompetence in a given area.

I was moping about how I was failing by not failing and generally wondering where to go next when I came across a philosopher who put his finger right on the main nerve. It isn’t the first time he’s put me on the right path when I needed guidance. Meet my spirit guide:

Yes, I’m perfectly aware he’s a cartoon dog created by Pendleton Ward and voiced by John DiMaggio. He’s also a perfect character to voice subtle wisdom. And here’s the quote that got me.

This works on two levels. First, it’s an acknowledgement that nobody starts out perfect, and it’s practice and effort that makes you better. But more importantly, sucking at something you thought you’d already mastered will open up new levels of complexity and new ways of thinking about what you’re doing.

Jake’s wisdom immediately cheered me up. I went out and brewed a batch of Belgian Witbier. I wanted to do something interesting, so I did a 5-step decoction mash (a complex technique that involves many steps of taking some of the grain mash, heating it and adding it back to raise temperatures, over and over again). I also added two kinds of dried orange peel and two different kinds of coriander, and a Saison yeast strain to kick up the spice.

It turned out terrible. And that’s great.

I learned things about the value of decoction mashing (low, in this case) subtlety with spices, and the lack of crossover between Saison and Wit yeast.

Most of all, I learned that I don’t have a magic touch or a lucky streak, and my beers can really suck when I lose focus, and that any pride I have is misplaced.

I followed that beer up by brewing a proper Saison, an Imperial IPA and a session beer. In every case I used new techniques, ingredients or yeast that I haven’t worked with before. I’m very lucky to have had the privilege of failure, the ability to make mistakes, see what they were, and to correct them. Failure makes me a better brewer, and I’m looking forward to screwing up next time–as long as I don’t run out of beer because of it!