Say ‘decanter’ and every wine drinker will know what you mean. They either visualise the never-used cut-crystal wedding gift on Mom’s china hutch (incidentally useless for decanting) or a stuffy British television show where the characters pass around a glass-stoppered vessel of port while harrumphing to each other about the imminent collapse of society. Whatever the image, the conventional wisdom is that decanting wine is accepted for letting young reds breathe and for getting old gunky reds off their sediment.

Funny thing is, there’s a bit of controversy about decanting. One of the most revered and famous winemakers on the planet (Professor Émile Peynaud) thought that decanting was the worst possible thing you could do, and railed against it. Of course, just being a professional French oenologist who shaped many of our modern ideas of winemaking means nothing: I think he was full of hooey. Who are you gonna trust, some French guy, or good old Tim? Okay, perhaps hooey is a strong word (anyone know what ‘hooey is in French? Sottise?) I confess I’m referring specifically to wine from kits, something on which, as far as I’ve been able to discover, Peynaud never commented.

With home winemaking in mind, let’s have a look at decanting, in history and in practise

Decanting in History

In the past there was always some sort of decanter in any wine drinking household. At first this was because wine was typically stored in large vessels, either giant clay jars, amphorae or barrels, and some sort of carrying vessel was needed to get the wine from the cellar to the drinker’s glass. Until the 17th century wine was never stored, aged or transported in glass bottles, although the ancient Romans did use blown glass decanters to serve their wine. You can tell that the early 17th century bottles were intended for serving wine rather than storing it, because they were often shaped like ‘onions’, with a globular body, flattened bottom, and a very short neck–a shape that would never lie on its’ side in a cellar, even if there were a cork to fit it!

In the 16th century the Venetians rediscovered glass-making technology, and their wares spread across (and were widely copied by) the rest of Europe. Because corks were an exciting and newly emerging technology at the time, nobody had thought of using them to seal wine bottles, so blown or ground glass stoppers were included with some bottles to seal them up, at least temporarily. With a custom made glass stopper for each bottle, it was imperative that the two not be separated–stoppers weren’t interchangeable. To that end, stoppers were wired or tied to each bottle. In order to facilitate this, a ring of glass was applied just below the top of the neck where the string was anchored. You can still see the vestiges of this on the neck of almost every modern bottle in the form of a tiny rim around the top.

In the early 1700’s people rediscovered something important: vintages mattered, and if you could keep some of your best wines well cellared, they improved dramatically. The best way to store the wine turned out to be in a glass bottle, sealed with that exotic new cutting-edge material, ‘cork’. While cellar ageing was great for improving wine, it also lead to another condition–layers of goo in the bottle. Fining, stabilising and filtration technology was not as advanced then as it is now, and many wines would throw sediment, tartrate crystals (‘wine diamonds’) or a haze during storage. The answer, of course, was decanting the wine into a clean serving vessel for the table, leaving the detritus behind.

Another benefit of this was the ability of the host or hostess to decant all of the wines being served at a dinner party well before the guests arrived. They could then be displayed on the sideboard or table, ready for each course in turn. This custom is where the practice of using decanter labels (the Victorian name for these is ‘bottle ticket’) came from. These are small metal nameplates hung around the necks of the bottles–it would be a terrible crisis for the party hostess to confuse the Madeira with the Canary before the toast course!

Modern Decanters

While any clean food-safe vessel of sufficient capacity can be used as a decanter, modern folks are usually intent on either separating their wine from sediment or giving it an airing. To this end, most decanters are made of clear glass and are approximately 30-50% larger in volume than a standard bottle of wine. With an eye to the airing thing, the design usually allows for one bottle of wine (25.6 ounces, 750 ml) to fill them exactly to their widest point. This ensures that the wine is presenting the largest surface possible to the air to allow it to pick up oxygen.

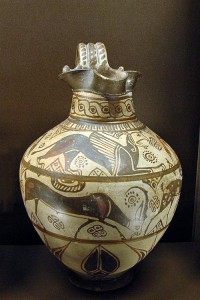

There are also cut-glass decanters, more for serving fancy spirits, and some specialty decanters that hold two bottles of wine (for magnums), some very pretty models shaped like Greek pitchers, with handles and pouring spouts, and some decanters even have perfectly rounded bottoms–so they can’t be put down on the table, and have to keep being passed until they are empty!

Decanting Theory and Practice One: Sediment

Virtually all modern table wine is intended for more-or-less immediate consumption, and will never have the chance to throw any sort of haze or sediment. Vintage Port, however, almost always throws a ‘crust’ in the bottle. This is because it’s bottled very early in its evolution. As many Vintage Ports need 10 or even 20 years before they’re ready to drink, this means that they will continue to evolve not just in flavour and aroma in the bottle, but also in appearance, dropping a thick layer of tartrate crystals, colour compounds and polymerised phenolics (tannins, mostly). If you just poured the Port directly from the bottle, you’d wind up with a pretty hefty layer of goo in the last three or four glasses. In this case, decanting helps present a wine in its best light.

Decanting to separate the wine from sediment is done very carefully. First, the bottle is brought up from the cellar and stood upright for 24 hours, to allow all the sediment to settle. Next, a scrupulously clean decanter is readied, and the Port is very slowly and gently poured into it. This can take as long as three or four minutes. The goal is to disturb as little sediment as possible. Towards the end of the bottle, the sediment will begin to flow down towards the neck. However, Port bottles have a strong drop-shoulder, and by keeping watch, you can stop pouring as soon as the sediment begins to flow towards the neck.

There are some gadgets that are designed to help with the process. The traditional candle held behind the neck of the bottle to help illuminate the flow of sediment has been replaced mostly by strong flashlights, but decanting cradles are still around. This gadget, looking like a cross between a dismembered music-box and a hand-driven apple-corer uses a mechanism to tilt the bottle with glacial slowness, to prevent any sudden tipping that could disturb the sediment. They’re not cheap, and most of the ones around are antiques.

Should you decant your Port before serving? If you’re the kind of person who collects vintage Port, you already have your own opinion on that. If you’re like most of us, making and enjoying Ruby and Tawny-style Ports from kits or home fruit, it’s probably not going to be necessary–but it does look fancy, and won’t hurt a strongly-flavoured, high-alcohol Port in the least.

Decanting Theory and Practice Two: Breathing

The most wide-spread reason for decanting is aeration, giving the wine a chance to soak up some oxygen, to ‘open up’ and express its aromas. On the surface, this sounds pretty good: the wine has been cooped up in the bottle, so letting it out to stretch its legs would make sense, right?

Well, according to some oenologists, wrong. According to these experts, post-fermentation oxygen exposure is virtually always detrimental, and the greater the exposure the more damage it does, driving off delicate aromatics and numbing the wines delicate bouquet. Only heavily sedimented wines should be decanted, they say, and then only at the very last minute before they’re served.

Indeed, for very old wines this is true. I was at a wine tasting in the early 90’s where a very rare bottle of Argentinean Cabernet Sauvignon from the 1950’s was poured. It was amazing at first, a rare and delicate wine with cedar, hints of blackcurrant, dusty cigar box, even rose petals lurking around. As I sniffed and swirled it over the course of four or five minutes the aromas got lighter and thinner until suddenly poof! It smelled of nothing except lightly vinegared water. It was almost like seeing a vampire getting trapped in the sunlight; it decayed away to nothing so rapidly. Decanting this wine would have doomed it to losing its character before the drinkers ever saw it.

Keep in mind, however, that most oenologists don’t make wine at home (hey, it’s their loss–I’m here when they want to try). If there’s one thing I’ve learned in the last 15 years of working in the consumer wine industry, it’s that people tend to drink their kit wines before they’re actually ready. Not that this is such a terrible thing–some wines taste just fine while they’re fresh and snappy with youth, and others, like the Mist-type fruit and wine beverages are meant to be drunk the day of bottling. However, the bigger, oak-aged whites and many of the reds really benefit from at least a year of age in the bottle, resting quietly and gaining strength for their unveiling. For these underage wines a little airing not only doesn’t detract from them, it also accomplishes the following:

- Separates it from any sediment (definitely an ‘oops’ in young wine, but if you decant it, no one will ever know!)

- If the wine has a small amount of trapped carbon dioxide (CO2) and is slightly ‘fizzy’, decanting can drive this off, making the wine smoother. Dissolved CO2 in solution forms carbonic acid, giving the wine a sharp ‘bite’. This is an issue that afflicts beginning winemakers quite frequently.

- If the wine has an appreciable aroma of sulphite, decanting can oxidise it and drive it off. Most kit wines have a carefully measured amount included, but if you think you can detect it, decanting will disperse the ‘burnt match’ character.

- Wines that are heavily oaked will lose some of the ‘Chateau Plywood’ character and show more of their fruit quality.

- Highly tannic red wines will lose some of their harsher bite, and present a fruitier, more approachable flavour and aroma.

Indeed, with very young home-made wines the improvement made by decanting the young ones can be quite dramatic. They go from closed, low aroma wines with a character that some people interpret as ‘that taste’ to fully open, approachable wines with a pleasant aroma, and only the characters associated with commercial wine.

Decanting Theory and Practice Three: The Going Gets Weird

If you’re a very serious computer geek, the name Nathan Myhrvold will be familiar. As the former chief technology officer of Microsoft, he was charged with applying his brains strenuously to important science-y stuff. In his retirement he didn’t leave his big brain behind. In addition to spearheading private initiatives on clean nuclear energy and geo-engineering, he wrote the book Modernist Cuisine, a bazillion page tome on applying science to food preparation. He caused quite a stir back in 2011 when he wrote a short article for Bloomberg Businessweek. In it he described a radical idea for decanting:

Wine lovers have known for centuries that decanting wine before serving it often improves its flavor. Whatever the dominant process, the traditional decanter is a rather pathetic tool to accomplish it. A few years ago, I found I could get much better results by using an ordinary kitchen blender. I just pour the wine in, frappé away at the highest power setting for 30 to 60 seconds, and then allow the froth to subside (which happens quickly) before serving. I call it “hyperdecanting.”

Your average winegeek will feel faint looking at that. I had my own gadzooks moment on reading about it, but I have since tried it many times. While Myhrvold suggests double-blind triangle tasting to confirm (where you taste three wines, two the same, one different, several times, served by someone who doesn’t know which wine is which, to eliminate bias) it’s such a simple thing to detect that I only bothered the first time.

It works, very well indeed.

Does this mean you should be putting your vintage Bordeaux in the Vita-Mix, as Myhrvold suggests? Not necessarily, as it’s actually very pleasant to allow a wine to open up slowly to enjoy its progression, it’s opening and changing over the minutes or hours. But if you’ve got a very young wine that’s stubbornly clinging to a closed and tenacious nature, and you own a blender . . . I guarantee you’ll notice an immediate change.

Addenda

My friend Larry pointed out that I’d mentioned a decanting doohickey ‘looking like a cross between a dismembered music-box and a hand-driven apple-corer’. I really should have included a picture to go with that imagery, and courtesy of another chum (thanks Glenn) here’s a shot:

Any questions about it–is it useful, is it relevant, is it necessary–are irrelevant. I need one.

Hooey (n.) “nonsense, foolishness,” 1922, American English slang, of unknown origin.

I’M A HELPER.

And, hey, I’ve got some chardonnay that could do with more aging. Think I’ll do an unscientific power-decanting this weekend.

Hey, I know hooey: I’m the hooey Master! French hooey is tougher, since I didn’t pay attention in French class, except to the teacher who was cute as a little French button.

Also, I’ll make sure I don’t use the blender I use for mincing garlic.

Depends on your attitude towards the ultimate flavour of the wine, I suppose.

I now have a use for the blender I was about to abandon due to the blades having 15 years of use and being unable to mush much more than a smoothie any more… awesome, thanks Tim 😀

Here it is, only 9:00 am and I am already learning things! Awesome! Of course, I’m supposed to be working, but still – learning is important.

The more you know . . .

Interesting article. Thinking of shelfing my decanter, now

I like decanting, on occasion. One place where it really helps is if you’re pouring from a magnum (1.5 litre) bottle at the table. Pour off 750 ml at a time and it’s much easier to top up the guest’s glasses.