Diversity in home winemaking is something that’s been on my mind. Since I’m in the single most privileged category of humans who have ever lived: white, male, heterosexual, nominally Protestant, not impoverished, educated, North American, English speaking, et cetera, I had better be thinking about it. If I’m not, I’m just wallowing in privilege. To paraphrase Louis CK, you can’t even throw a slur at me–I am an Apex person in our society.

This gives me a congenital blind spot about diversity–not because I’m against it, nor because I consciously want to maintain a privileged status quo beneficial to me, but if you want to talk about how other people are involved with water, the last person you would consult should be a fish. I am that fish, swimming happily in a gloriously warm sea of perfect contentment.

Another spot where I have to check myself is my citizenship. Canada is an officially multicultural country. Unlike America, we don’t operate as a melting pot, with the refiner’s fire purifying the dross of external cultures and races and making ‘citizens’. We’re much more like a tossed salad, complete with leafy greens, vegetables, croutons, zesty dressings and accoutrements, all contributing singular and identifiable characters to our country and our communities.

It’s actually built into our charter of rights (section 27) and we’ve even been described as “the most successful pluralist society on the face of our globe”. I don’t happen to think we do it perfectly, yet it shapes how Canadians think people behave everywhere, and it leaves the privileged with the idea that the whole diversity thing is handled: yup, nothing to see here, that’s all settled, nobody should complain, and if they do, they must want more than their fair share, because we got that behind us already, right?

Theoretically, but not always in practice. A dozen years ago it occurred to me that I worked in a relatively mono-cultural, mono-racial hobby, and that I was mainly surrounded by people more or less like me. I’ve always tried to make everyone who expressed an interest in home winemaking feel welcome and respected, and I’m delighted to learn about people who have ethnic and cultural lives and traditions different from mine. But still, there’s little diversity in the hobby and the industry.

After I became aware of it I had to restrain myself a bit. Whenever I saw someone visibly different from me I had the urge to smother them in hugs and attention. It’s not that I wanted to bend over backwards to ‘correct’ or ‘balance’ anything. I was just grateful that there were folks bucking the trend. Just recently I was provoked by a very thoughtful article on diversity that pushed me articulate my feelings more strongly.

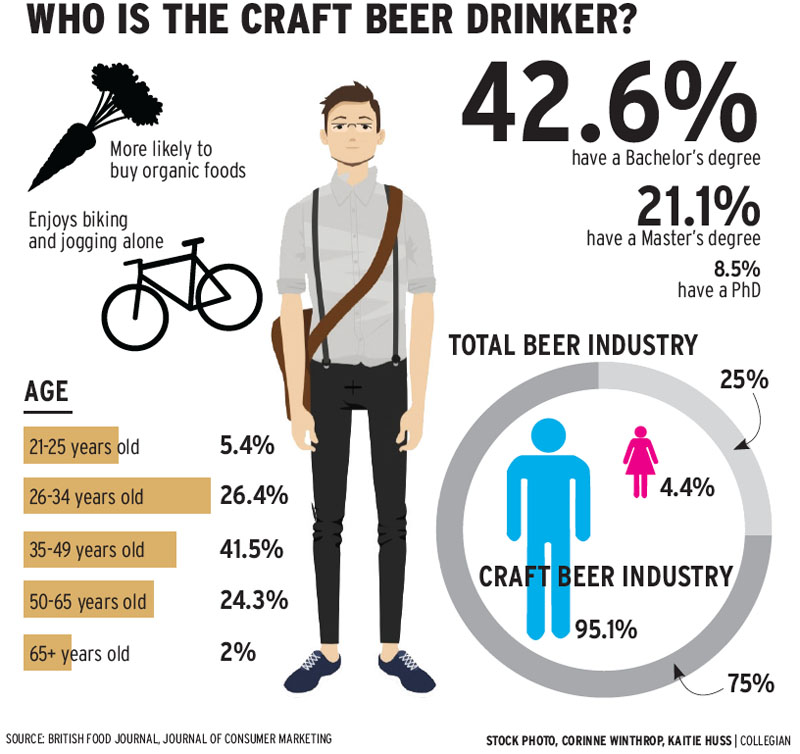

The article that spurred me popped up in my news feed last month: THERE ARE ALMOST NO BLACK PEOPLE BREWING CRAFT BEER. HERE’S WHY, by Dave Infante. Infante is writing about the Craft beer movement, but his observations transfer very well to home wine and beermaking.

He gives some solid reasons for a lack of black participation in the Craft industry:

- A sense of exclusion from the culture: “God forbid you want a ‘regular’ beer instead of an 18% homebrewed bacon-infused IPA. You’d get an earful from the closest neckbeards about how you just have to ‘work’ through the taste.”

- Lack of welcome for black drinkers : ” Dennis Byron. . . told me that while “there are no ‘White Only’ signs” in craft beer, the market still has a long way to go to court black drinkers.”

- Racism in the historic beer industry, dating back to the post-prohibition reopening of American breweries

- Economic factors (breweries take a lot of money to open, and if you want fast returns and a rich lifestyle, don’t open a brewery)

The exclusionism is not a race issue–snobby, unwelcoming beer geeks have been around as long as we’ve had modern craft beer, whether it’s a leather-palated IPA fanatic who can’t taste anything below 100 IBU’s or the newly-minted sour enthusiast who thinks you ‘just don’t get’ why you should drink a bottle of carbonated vinegar. They’re capable of driving even the most inquisitive and open-minded tyro away from beer and into a more welcoming beverage category.

The lack of welcome for black drinkers and the inability or in attention to courting them is deeply institutional. There are only a handful of non-white brewers in the craft scene (Garret Oliver is the most prominent, but he’s been shouldering the load mostly by himself since the 90’s) and while I haven’t seen any ‘Whites Only’ signs, a lack of overt racism isn’t the same thing as open arms. I’ve yet to see any sort of marketing or positioning that reaches outside of the box to any minority community. Craft breweries simply aren’t thinking about it.

The history of racism in commercial brewing is sad and troubling. The world was different then, but in the decades that have passed there has been no meaningful address to the past. Since there weren’t any Craft brewers around at the time it can’t be hung around their necks, but if we’re going to inherit the beer industry, we need to take on its entire legacy, not just the good parts, and do what we can to make things better.

The economic factors are an over-arching theme in our society. Lack of access to funds affects everyone trying to open breweries, but minority groups have a proportionately harder time due to historic economic disparities.

There are very few exceptions to the whiteness in the industry. Garret Oliver seems to shoulder the load for the most part, and Black Frog Brewery in Toledo is minority owned, along with 5 Rabbit Cerveceria in Chicago. But it’s a handful of exceptions, not dozens and certainly not hundreds.

There is an NPR article on diversity in brewing that makes a very strong point about roots of brewing:

Looking at the nation’s community of home-brewers also sheds light on the matter, says brewer Jeremy Marshall, of Lagunitas Brewing Co.

“Craft brewing is rooted in home-brewing,” Marshall says. “And if you look at home-brewing, you see nerdy white guys playing Dungeons and Dragons and living in their mom’s basement, and I know this because I was and am one of them.”

Point taken: craft is definitely rooted in home fermenting, and home wine and beer makers are overwhelmingly white. But it doesn’t have to stay that way if we don’t want it to.

Those are all legitimate issues, but after them Infante gets around to asking the big question: does it even matter? After all, if the black community is fine with neck-bearded white guys lecturing each other about sours and Saisons, why should anyone care? He goes on to ask if the topic isn’t “just a big, foamy glass of white guilt masquerading as a beer story?” If it was, then my own feelings amount to an assumption of The White Man’s Burden, extending the cultural imperialism of the past with malt and hops.

Fortunately, Infante and I both think it does matter, for two very important reasons. First, by staying homogenous we lose out on people who are talented, passionate and dedicated to what they do. He cites Annie Johnson, a black woman who won Homebrewer of the Year in 2013, with a beer in the most difficult category of all, light Lager (thirty years on, I’m just getting a handle on the style–it’s a beast. This is the equivalent of climbing Everest in a Speedo and sandals, or running a marathon in a suit of armor) and yet, despite accolades like Pilsner Uquell’s head brewer telling her that hers was the best beer he’s ever had, she can’t break into the brewing world. This is a waste on a monumental scale: I want to drink her beer.

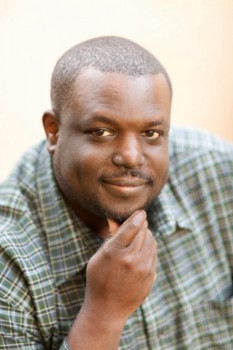

In home winemaking, there are people like my friend Ron Scovil. If you want to read Ron’s story in his own words, it’s here. I don’t want to overwrite his voice, but to compress it down, I met him in Colorado back in 2007 at a wine tasting/lecture I was giving. As soon as I tasted his first wine, I knew he had ‘it’–the ability to coax both flavour and balance from his raw materials. I knew he had what it takes to be a star winemaker, and I told him so and encouraged him to pursue it. (I also met his mom, an excellent lady–meet her and you know where he gets his good qualities from.)

Ron won Best of Show in Colorado for his wine twice and his mead three times in a row and wound up on the front page of the news in Napa, and on USA Today and NBC Sunday. Despite other winners getting a plaque in the sponsoring brewery and their winning brew on tap, Ron was left out. He persevered and won best of class and double-Gold as a professional winemaker in Napa. Again, despite his results he was unable to raise capital for his own operation or break into the industry, and talks about bigotry he suffered from people in the industry.

If there’s one thing my hobby and industry needs, it’s more Ron Scovils. Because talent like that should be welcome wherever it goes. I want to drink his wine, and the fact that I can’t is a waste of talent and skill that is a sin.

And that leads to the second reason why diversity matters: unless we open up and welcome everyone to our hobby, we risk perpetuating a larger social injustice, that of institutionalised racial inequality. If we can bring more diversity, broader ethnicity into our hobby, and make their presence a normative situation, then we can have an impact way above our weight in greater society.

Can our hobby really change things, have a big impact? Only 50 years ago there was still official segregation in the USA, and it took a fierce fight, sacrifice, and the collective will of incredibly brave men and women to make progress against it. But the small things, what we do in our own homes and in our own lives, and how we treat and deal with others, where we make room in our hearts and minds for new ideas, and for new people to come into that world, into that life, that we as individuals can slowly and patiently and change the world we live in. To paraphrase Infante, home wine and beer making isn’t the source of the problem, but it can become a part of the solution.

Which is the next step, promoting diversity in home wine and beer making. The first step to solving any problem is to recognise that you have one–and we do. The next is to make sure you stop making the mistakes and assumptions that lead you to the problem in the first place, and after that to make the changes you need.

For my part I’m going to keep thinking about diversity, and I’m going to keep welcoming everyone to the fold of making their own beer and wine, and keep listening to their stories. And when and where I can, I’m going to use whatever influence I have over my industry to promote diversity and encourage everyone to join in. Diversity encompasses acceptance and respect. It means understanding that each individual is unique, and recognizing our individual differences–and I’m certain that it’s the right thing to do.

And I’m going to continue to do what I think is my real job: encouraging people to make their own wine and beer, to share it with friends and to make it a part of their life, family and community–no matter who they are. Because a shared love knows no race, creed or ethnicity, and everyone should be welcome to share their passion and pride in accomplishment.

Note that with the exception of quoted material, these are all my own thoughts and I’m responsible for them, but thanks are due to my friends Fred and Nanette for taking the time to look at an early version of this–your help was invaluable.

If anyone would like a larger discussion of race, this is a powerful and thought-provoking discussion.