You can find any number of articles on filtering wine—a quick search on the inter-webs yields something like forty-four million hits—and probably double that number of opinions on the topic. Winemaker magazine has run many articles on filtering, including an excellent one by their regular kits columnist, what’s-his-name. So there’s no dearth of information on the topic.

What there is, in fact, is a surfeit of information on the mechanics and execution of filtering, the how-to side of the process. What you don’t see very often is the other side, the philosophical, the ‘why-to’ side, or the ‘why-not-to’ side. That’s up three sides now, making it perilously close to geometry, but there are a bunch of issues surrounding filtering that come up over and over again in winemaking discussions.

- Do I have to filter my wine?

- What are the benefits to filtering, long and short-term?

- What are the potential downsides to filtering?

- Does filtering strip colour, flavour or aroma from a wine?

- Do I have to use fining agents if I’m going to filter anyway?

- What’s the best filter to use?

With these questions usually come some very strong opinions. In some cases the strongest opinions come from people who’ have a little knowledge and the proverbial danger that comes with that, but opinion isn’t limited to them: some of the most knowledgeable winemakers, making some of the most expensive and well regarded wines in the world have very strong opinions as well, and some of them directly contradict each other.

In fact, the Oxford Companion to Wine (full disclosure: I’m a contributor to that august tome) even lists filtration as a ‘controversial’ subject. From the OCtW:

Filtration of fine wines is a controversial issue. While it may be a necessity for ordinary commercial wines, it is widely thought that too heavy a filtration can indeed rob a fine wine of some of its complexity and capacity to age, not to mention some loss of colour, particularly a red wine as subtle as some fine red Burgundy. Some commentators and winemakers claim that filtration of any sort is harmful: it is not uncommon to see the term ‘unfiltered’ used as a positive marketing term.

Gadzooks! Loss of complexity! Loss of capacity to age! Any filtering harmful! Is there no upside to filtering? Well, maybe, as the entry goes on to say:

However, the possible negative effects of filtration should be weighed against the very real risk of microbial contamination or instability, particularly where perfect storage or transport conditions cannot be guaranteed. An unfiltered wine throws a much heavier crust, or sediment, than one that has been filtered.

What to think? Well, first of all, keep in mind that the venerable Oxford is almost exclusively concerned with commercial winemaking. Out of thousands of entries there’s only one on home winemaking, and until I re-wrote it, it never mentioned kit wines and only devoted half a sentence to ‘concentrate’, so their opinion might be a little fluffy around the edges, not close to the rich, meaty centre of winemaking where us consumer winemakers make our bones. We don’t need a marketing department to tell us how our wine tastes when there’s a perfectly good glass right there at our elbow.

Second, I’m discussing only the filtering systems and processes available to home winemakers–yes, cross-flow filters are like amazing magic boxes that can accomplish astounding feats of clarity, but until they drop below $20,000 and require less than 100 gallons to prime the pump, they’re not going to be of any use to real, live home winemakers.

1) Do I have to filter my wine?

Nope, at the end of the day filtration isn’t necessary. In the 10,000 year-plus history of winemaking, filtration has only been possible in the last century or so, after the advent of industrial processing and a firm understanding of the microbiology of wine (thanks, Louis Pasteur!).

With modern winemaking technology, wine kits come almost completely free of suspended solid material. Precisely calculated fining agent use, in the form of bentonite, Chitosan, isinglass and kieselsol, deals with any colloids (like proteins) and 99% of the yeast in a very short time, leaving the wine clean and quite clear.

So you don’t have to filter if you a) don’t have a filter, b) don’t want to go to the trouble, or c) don’t care. You’ll still have clear, drinkable wine.

2) What are the benefits to filtering, long and short-term?

In the short term, you will be able to expect what the industry calls ‘star bright’ wines. I said the finings leave the wine clean and quite clear, but not completely clear. After fining there can still be tens of thousands or even millions of yeast cells still floating around in your wine. There can also be unstable colloids floating around. These materials will take the edge off of clarity. There are two analogies that fit pretty well here. First, if you’re an eyeglass wearer, you know well that you can look through your spectacles and see clearly almost all of the time. But if you take them off at any random interval and have a look at the lenses, they can be pretty smeary and icky. A quick polish will allow you to see more clearly and accurately.

The second analogy works even for the perfectly-sighted: the difference between a well-fined wine and a filtered wine is the difference between a freshly washed car and a freshly waxed car. They both look good, and they both look shiny, but the waxed car really looks spectacular, and is much more appealing to most people who will look at it.

Long-term you can look forward to greater stability. Stability in this case is defined as the wine not changing in flavour or appearance during storage in the bottle. As the Oxford notes above, there are issues with microbiological stability and with deposits or sediments in unfiltered wine.

Microbiological stability merits a mention, but not too much concern. Since all kit wines are pasteurised at packaging, there are very few potential contamination organisms that will show up in your batch. The one place where filtration provides extra protection is for wines that have residual sugar, or sugar added post-fermentation via ‘F-packs’, ‘sweetening packs’ or ‘Süsse-reserve’. Putting these wines through a filter will help reduce the yeast population below the level at which they can ferment sugar into carbon dioxide and alcohol, keeping your sweet wine from turning into fizzy, bottle-shattering dry wine. Toss in a bit of sorbate to keep the remaining yeast from breeding back to culture strength (from where they can start making fizz-and-booze again) and you’ve got increased stability over the long term.

Another long-term benefit is in the appearance of the wine over time. Deposits and sediments can (and indeed, almost always will) form in fined but unfiltered wines over a long enough timeline. These deposits show up in reds as a thin layer of purple or red material on the bottom of the bottle or in a line along the side. In whites they appear as white-ish or beige. They can be dead yeast cells, polymerised phenols (a kind of tannin that’s gooped up and settled out) or (in reds) pigmented tannins. Pigmented tannins occur when tannins bind with anthocyanins.

If you’re getting a sore head from all the polysyllabic terms here, tannins are (mostly) the compounds in red wine that give astringency and mouth-feel, and anthocyanins are colour compounds. The process is insanely complex, from a chemical point of view, but when they bind together over time they can settle out as a very fine, almost paint-like layer of muck.

Filter, and you’re not likely to see any fall-out in your bottles over the medium (three to 5 years) term, and much lower levels after that.

3) What are the potential downsides to filtering?

Surprisingly, they’re pretty much the same as the downsides for any handling or processing operation in winemaking, from racking to fining and stabilising: the chance that you’ll introduce a contaminant or too much oxygen into the wine, causing an infection or oxidation.

Both of these are easily avoided. First and foremost, as in all aspects of life, with winemaking cleanliness is next to goodliness. Every piece of equipment that comes into contact with your wine must be clean—free of visible dirt or debris—and sanitised—treated with a chemical sanitiser to kill or suppress bacteria. Filter machines often have a lot of hoses, clamps, crevices and irregular surfaces, so be sure to disassemble them and give ‘em a good scrubbing, treat them with sulphite or other suitable winemaking sanitiser/suppressant, and rinse the dickens out of them.

As for oxygen, filtering agitates wine as it travels through pumps, hoses and filter media, but doesn’t necessarily introduce oxygen into it. Most filter set-ups are positively pressurised, meaning they use a pump to force wine down a hose and through the system. If there is a leak somewhere in the filter between the pump and the carboy the wine is going into, it’s going to squirt wine out, not suck air in.

The only real danger that using a filter will add oxygen is if you run the output hose down the side of the receiving carboy, where it can fan out and expose an enormous surface area to oxygen pick up—gently place the output hose directly into the bottom of the carboy instead, and allow the tip to submerge as it fills, keeping everything as quiet as possible.

What you really have to watch is that there is sufficient free sulphur dioxide (metabisulphite) in the wine to protect it during handling. This will be the amount included in the kit, added in full, at the appropriate time. Just a hint: if your kit has a note in the instructions about optional added sulphite for ageing terms over six months, add it before you filter, even if you’re going to drink the wine up sooner. This is prudent because the very small extra amount the instructions ask for, usually a quarter-teaspoon, which is less than a gram and a half, won’t change the flavour or aroma of the wine, but will make sure the extra handling that filtering represents doesn’t cause harm.

3) Does filtering strip colour, flavour or aroma from a wine?

Yes and no. But mostly no, and the aroma and flavour part is strictly temporary, and the colour part is good. I’ll explain, but first I’ll qualify: I’m telling you the strict truth, for people using filters available to people making their own wine at home. You might read contradicting opinions somewhere else but keep in mind two things: first, some of those opinions will be from people who have access to commercial filtering equipment and processes, which can be vastly more effective at removing things from wine. Second, they’re probably wrong.

Colour

The kinds of filters available to home winemakers operate on the micron scale, with the tightest, most efficient filters stopping somewhere above 0.2µ, about two-tenths of a micron. Your typical yeast cell is around 0.45µ, and a freshly budded daughter cell (they grow up so fast, sniff) is down at the 0.2µ mark. It’s far more common to see filters that allow the passage of material as large as two to four microns in size.

Colour molecules, the aforementioned anthocyanins, are not on the micron size. They are so very much smaller that their structure can’t be seen with a microscope. They’re so tiny that in fact they will sail straight through a filter pad or cartridge entirely unimpeded—you can’t filter them out.

Which begs the question, for anyone who has ever used a filter on a red wine, why do the pads come out stained with colour? Those stains aren’t pure, happy colour compounds: they are colour compounds that have already bound to other kinds of goo in the wine. When bound to tannin, they’ll fall out later as a deposit (mentioned above) and when bound to a colloid, they’ll fall out as sediment. This is a vast over-simplification (I specialise in those) but the core truth is that you cannot filter out colour with civilian filter pads—not any colour that wouldn’t fall out on its own anyway.

Flavour and Aroma

What goes for colour compounds goes for flavour and aroma: they’re just too small to stick to filter pads. And yet anyone who has ever filtered a wine has almost certainly noted that it tastes notably less distinct and aromatic post-filtering.

This is a complex phenomenon wine, referred to under the catch-all phrase ‘bottle shock’. A couple of explanations are popular. First, a dose of sulphite (usually added at bottling or filtering) mutes the flavour and aroma of the wine. Seems plausible enough, and easily observed by anyone who has ever tasted a wine right after sulphiting it.

Second, if a wine gets a significant dose of oxygen during handling, some of the oxygen can combine with ethanol and other alcohols to form aldehydes, which really cramp a wine’s aromatic styling. The good news is, both of these conditions are temporary. Give the wine a few weeks rest, and often only 24 hours will do it, and the aromas and flavours snap back into focus, good as new, with filtering not to blame after all.

I said earlier that anyone who disagrees with me is wrong. I still think that, but there is a way in which they’re reaching towards a sort-of truth about filtering and removing desirable compounds from wine. When a wine, particularly a red one, is very young, you want to get it off of the gross lees and then the fine lees quite rapidly, with several rackings taking place in the first year. This prevents yeast cells from decaying and transferring their flavour into the wine, and prevents all kinds of grape pulp and vineyard muck from getting funky as well. But you don’t want to strip the wine clear of all compounds right away. There are extremely complex chemical reactions and biochemical processes that can benefit from the presence of solid material dissolved and suspended in the wine as it goes through elevage (upbringing).

That doesn’t add up to an indictment of filtering, however, it just means that you should filter as the last step in your process before you go to the bottle—too early and you might cheat an ageing/elevage process of some compounds that could help.

5) Do I have to use fining agents if I’m going to filter anyway?

YES! You can’t filter a wine that isn’t already really, really clear. The amount of yeast and good in suspension would clog a filter up so badly that you’d spend more than the cost of the wine kit itself in filter pads before you got to the end.

If we go back to the car analogy, you can’t wax a car that hasn’t already been washed thoroughly: waxing isn’t to remove dirt it’s to put a final polish on the car. Filtering isn’t to clear wine it’s to put a final polish on it right before bottling.

6) What’s the best filter to use?

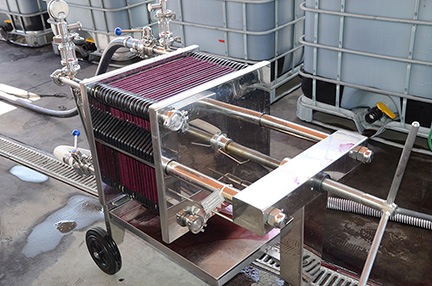

The most common filters available to home users are depth filters with plate and frames and positive displacement pumps. This means they’ve got some kind of structure of layered plates that trap cellulose pads in between them and the wine is forced through the pads by a pump that pushes it down a tube. There are others, including ones that use a vacuum to pull the wine through a plate and frame, membrane filters that use a setup identical to home water-filter cartridges, either with a pump or a vacuum, and even manual ones that rely on gravity to dribble the wine through a pad set-up.

Commercial wine filters can be much more complex, but most of them you can’t afford to switch on for less than a few hundred gallons of wine—a single 6-gallon/23 litre batch wouldn’t even prime some of the pumps. Things like cross-flow filters, centrifuge decanters, pressure leaf filters and rotary drum vacuum filters are amazing technology, but for most of us rather like swatting a housefly by dropping a mountain range on it.

I’m big on positive displacement plate and frame filters. They’re simple, very easy to set up and use, widely available, and ideal for our purposes. They come in sizes ranging from just smaller than a toaster, suitable for one or perhaps two batches at a go, to models big enough to do 20 gallons in a reasonably short time, and others intended for higher volumes that can filter a carboy sparkling clear in under 30 seconds. I own examples of all three, and they’re fine machines.

They’re called depth filters because the pads used in them act like a sponge, soaking up the wine and wringing it out clean on the other side, with the ‘sponge’ part retaining the cloudy goop. This makes them capable of taking quite a bit of muck out of the wine before they clog up. When they do, you toss ‘em out, because they’re cheap.

There’s no objection I can think of to using a vacuum system, set-up to pull wine from one carboy to another, with a plate and frame in between, other than an incremental increase in complexity while using it—if you’ve got a vacuum pump, more power (power vacuum?) to you.

But I’m not big on membrane filtration. Filter cartridges are best suited to water or air filtering, where they have to deal with fairly low levels of material. The issue is that membrane filters act as a screen-door, rather than a sponge. They usually have a fan-folded cartridge that almost behaves like a two-dimensional object. Anything larger than the holes in the membrane piles up on one side and clear wine passes through.

That is, until the cartridge membrane is completely blocked: because it’s a screen, there’s no depth to soak up lots of goo. After that you have to change it, or clean it before it can filter more wine. This can be done, but handled carelessly, as by backflushing with too much pressure, cartridge integrity can be compromised, allowing material to pass through.

And cartridges are much more expensive than filter pads. There are inexpensive examples, but they won’t be as effective or as strictly rated as more expensive ones. There’s not enough room in this article to discuss the difference between nominal and absolute micron ratings, but when you buy inexpensive cartridges, you’re getting pretty much what you pay for. It’s kind of the ‘toner model’ of computer printers—the money in cartridge filter systems is made in replacement cartridges, not in the actual system itself, so that’s where you pay if you purchase one.

It should be pretty obvious after these points that I’m a fan of filtering, and mostly with positive displacement depth filters. But you would be surprised how often I don’t filter. A lot of the time I’m too lazy. My reds sit for a couple of years before I get around to them, and by that time I’m out of wine and in a hurry, so I just get them in the bottle and pretty immediately into the wine rack. I’m more likely to filter whites, but even then my slack attitude towards a production schedule has me bottling without filtration at least part of the time. But with that, I have to put up with the occasional deposit in the bottle, which is fine for me, but puts a crimp in giving away bottles or sharing with others.

In the end, whether or not you should filter should come down to your own preference, your tolerance for extra processing steps, and the attitudes of those who will be consuming the wine—but don’t worry in any case: filtering won’t hurt your wine in any way, and can help improve the aroma and maintain its appearance over time.

Have you ever tried to just filter half or 2/3rd filter your batch of 6 Gallons? For age worthy reds I fund it often reduces enough the sediments while leaving elements that helps continue develop complexity while aging in the bottles.

You did not touch the question of the cold stabilization. For home wine makers lucky enough to have an old spare fridge in the basement, this is a process that could help clarify the wine, if it is degassed properly, and even more if done under negative pressure. I made a few years ago a buon vino bung airlock connected to a Seal air pump stopper that allows me to keep a wine under a certain vacuum while my white wine is cold stabilized for 2 weeks in the fridge at around 35F. The wine takes complex flavors from the lees very quickly. Filtering after this process allows certain complex aromas to stay quite clear. Sometimes my white wines are so clear after cold stabilizing that I just bottle them without filtering, but I prefer to filter my white wines.

Daniel,

True complexity is not derived from suspended solid material in the wine: it’s just floating crap, and once it’s soaked in the wine for a couple of months, it doesn’t participate any longer in a deeply meaningful sense, and the presence of suspended solid material is a flaw covering up the true nature of the wine–so, like all fine wine producers, I filter 100% of the wines that I filter.

Sur lie ageing is the process by which the yeast degrades and the cells burst, expelling their contents (mainly mannoproteins and amino acids) into the wine, adding mouthfeel and a savory character. This takes a few months at room temperature, and a significantly longer time at cold temperatures–autolysis pretty much stalls below 4C.

While chill stabilising can help precipitate colloidal proteins, it can also cause the wine to stop clearing,, especially if an organic fining agent (gelatine or Chitosan) has been added. A period of cold stabilisation can be useful, but it’s not a substitute for filtering.

Tim