For those following along at home, you can check out my mead series here

- Making Mad Mead Part One

- Making Mad Mead Part Two: Honey, I’m Home

- Making Mead Part 3: The Meadening

The generalized clamour for my head (preserved in a jar of honey) has died down, but I’m hopeful that with my descriptions of filtration and preservatives (as well as lots more sugar) will stir that all up again.

When We Last Left the Barkshack . . .

. . . it was fermenting strongly fizzing away for five days. I had a look at it every day, and when the vigorous fermentation dropped off, I took a specific gravity reading.

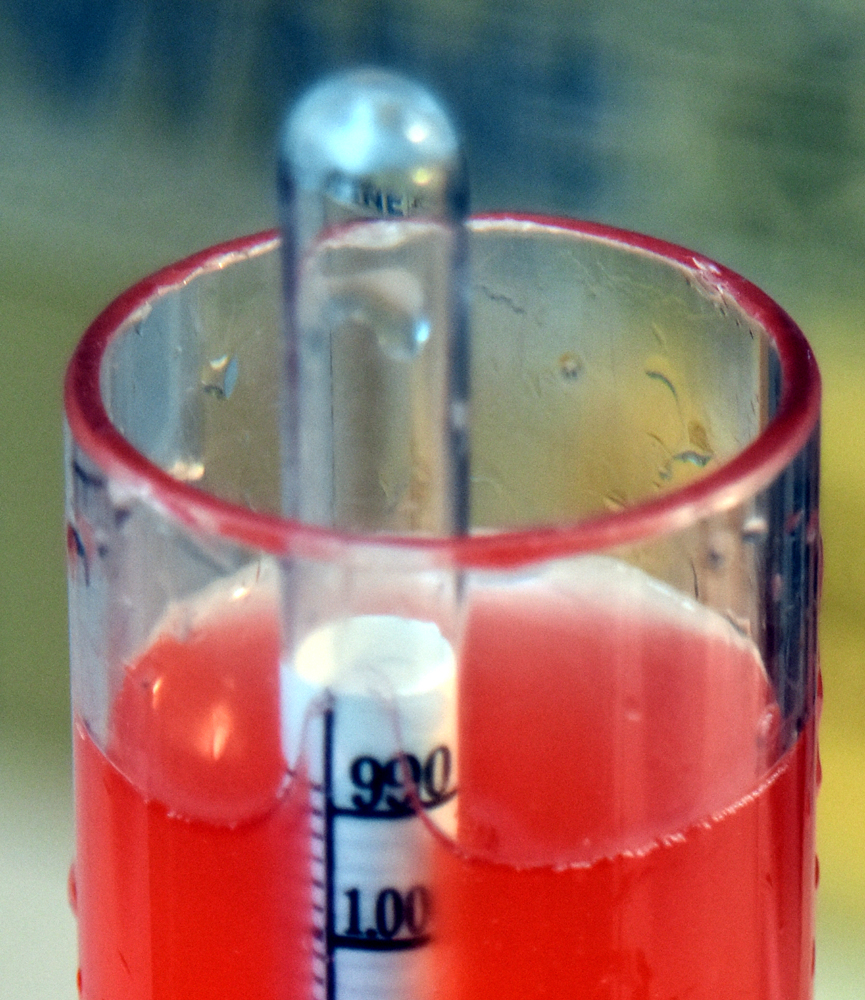

The first reading was 1.044 and now it was at 0.994, indicating complete dryness and an alcohol by volume of around 6.5%. That was a little more than I was expecting, as it had fermented out very low–the Saison yeast appears to have had a powerful and thorough effect!

The colour was great, the aroma was fantastic, but the flavour was dry beyond words. It wasn’t overly acidic, and the tannins derived from the raspberry seeds weren’t overwhelming (on the contrary, they were a like a backbone running through the mead) but it wanted some sweetness to bring out the character of the fruit. Interestingly, it had a light but definite honey aroma and flavour. I was pleased that it carried over the fruit, ginger and lemon notes as it really added to the character of the mead.

Adding Mad Adds

I hit it with my standard winemaking processing addition for fruit wines that I wanted to clear in a hurry, sorbate, sulphite, and finings. The three need to be done to any wine that’s going to be back-sweetened and not Pasteurized or sterile-filtered.

Sulphite stuns yeast and forces some cells to dormancy while preventing oxidative damage. Without sulpite additions the mead would lose that gorgeous colour and start losing flavour pretty rapidly, especially after getting exposed to oxygen like I was planning to do with it (more on that below). Since the mead was at a pH of 3.2 I settled on a single dose to bring it up to 50 PPM FSO2, counting that some would get burned off in processing and absorbed by oxygen extant in the mead already.

(If you’re not a fan of sulphite, I don’t actually care. If you’d like to argue with me about it, I don’t do that because there’s no defensible argument against correct sulphite usage. Sulphite is wonderful, and everyone should eat some every single day–oh wait, you do, because it’s in everything, including wines labeled ‘No Sulphite Added’. Want more info? Check out my awesome blog over at Master Vintner: Lies, Damned Lies, And Sulfites: The Facts)

The finings remove colloids, proteins and other material from solution, making it clear, but more importantly from a stability standpoint, they remove yeast cells, and that’s part of the strategy to get the mead stable enough to bottle. A good fining regime can reduce the yeast population to the point where they will no longer make alcohol and carbon dioxide, even if there is enough nutrients and food for them to do so.

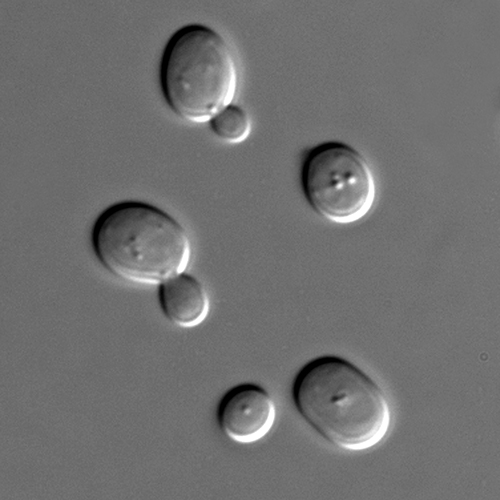

This is because yeast has two different schemes that are in operation in an alcohol fermentation. First, they breed up to culture strength, which is on the order of 10 to 20 million live yeast cells per millilitre of wine (or beer or whatever). When they hit that mark the population levels are too high, so they stop breeding. It happens all at once, and while it’s got to be some kind of chemical signal that does it, nobody has caught them at it yet.

After they stop breeding, they change their metabolic pathways and start turning sugars and nutrients into carbon dioxide and alcohol, rather than into millions more daughters. They’re ruthless, but practical. When they run out of food, they mostly go dormant, and a good percentage of them die. Between the sulphite stunning them and the finings pancaking most of them down to the bottom, they cease most activity.

But in the next stage, when we add back sugar to balance the flavour, if there are any yeast cells present, they will start breeding again, and when they hit that magic 10-20 million mark, the wine will go cloudy and re-ferment. And that’s where sorbate comes in.

What is Sorbate? What Does It Do?

Sorbate is a polysaturated fat in the form of sorbic acid (it’s made into potassium sorbate by reacting it with potassium). It’s found in blueberries, huckleberries and mountain ash berries in large amounts. It’s a food additive recognized by Health and Welfare Canada, and it’s classified as GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) meaning it’s pretty darn benign. One of the more thorough studies I’ve read showed that the only side-effect to large-dose feeding of sorbate to rats was a slight extension in life span (attributed to a protection against lung infections engendered by the sorbate).

Here’s the fun thing about sorbate: it doesn’t kill yeast. It doesn’t even make it late for work. What it does, is prevent yeast cells from budding off new daughters. It’s birth-control for yeast. That’s why it’s so useful. When you get the yeast population below the fermentation level, then add sorbate, the yeast can’t climb back up to the point where they can start making carbon dioxide and alcohol, and they leave the sugar and nutrients alone, so the wine doesn’t change character or flavour/aroma.

The Additions

After the sulphite, I added 250 PPM of sorbate and a dose of gelatin finings. I chose gelatin because it’s relatively strong as a fining agent, and because it reacts strongly with tannins, meaning it would tame the raspberry seed tannins a little, and work with them to clear the mead. I let the wine settle for ten days, and then went to the filter.

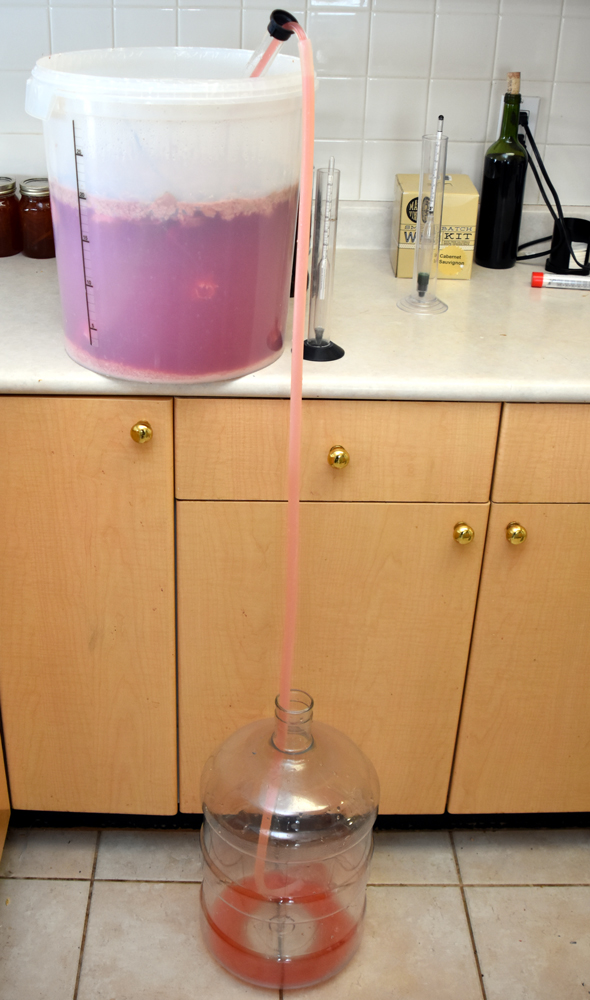

Filtering and Back-Sweetening

The mead wasn’t completely clear, but it was Friday, and I was heading down to the Pacific Northwest Homebrew Conference on Monday, so I rammed it through my filter anyway. I don’t recommend this: filtering should only be performed on clear wine/beer/mead in order to polish the appearance. Being as I was in an all-fired hurry, I did it anyway.

I did achieve a beautiful, sparkling clarity, but more importantly I reduced the yeast cell populations to a very low level, ensuring that with proper care I wouldn’t get re-fermentation.

The mead was still very tart and crisp, but what I was shooting for was lively, crisp and luscious. I dissolved a kilogram of sugar in 500 ml of water, along with a pinch of citric acid, to make invert syrup. I’d like to tell you how much I used, but I did it to taste and some of the invert went into another project, so I can’t be sure how much went where. I’d say about 2/3 of it went into a 19 litre Corny keg, gently stirred.

I banged the keg into my keezer and attached it to my CO2 system at 30 PSI and left it until Sunday afternoon, when I grabbed a glass to see if it was going to pass muster.

Oh yeah. The glass looks cloudy, but that’s condensate: the mead is perfectly clear. It was slightly overcarbonated, but that was handled by blowing the pressure down and leaving it to stabilize on its own. It was fresh, crisp, lightly but positively gingery and redolent of raspberry, lemon and honey.

Next step, off to Portland to talk to a roomful of eager meadmakers.